The Telegraph on the Death of Rev. John Stott

The Reverend John Stott, who died on July 27 aged 90, was one of the most influential Anglican clergymen of the 20th century; indeed, in 2005 Time magazine declared him to be one of the 100 most influential people in the world.

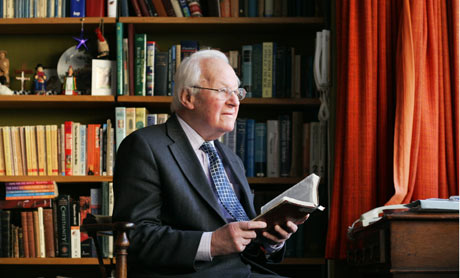

The Reverend John Stott Photo: KIERAN DODDS

The Reverend John Stott Photo: KIERAN DODDS

July 28, 2011

Stott was rector of All Souls Church, Langham Place, in the West End of London from 1950 to 1975, and this was the only church in which he served. He had been its curate for five years before he became rector and had attended services there as a child. He accepted no ecclesiastical preferment .

When Stott was ordained at the end of the Second World War, the evangelical wing of the Church of England was small, introverted, backward-looking and divided. Fifty years later there was an evangelical Archbishop of Canterbury; several diocesan bishops of similar convictions; and in all parts of England a network of dynamic churches inspired by the evangelical spirit. Moreover, these churchmen and churches had a marked affinity with their early 19th-century forebears whose leaders had provided the driving force behind the anti-slavery movement.

The change came about largely through the inspired leadership of John Stott. He turned his own church, located just a few yards from the headquarters of the BBC, into a showplace for a renewed form of evangelicalism. Strong lay leadership at All Souls set him free to become the trainer of others - in particular a new breed of young clergymen who had been influenced by the Christian Unions in their universities and by the Billy Graham Crusades in the 1960s. In the end, Stott viewed the world as his parish.

Stott was in constant demand for the leading of missions and courses in most parts of the English-speaking world, and from 1975 devoted all his time to this. He was a compelling preacher and spoke in a distinctive style, modelled, it was said, on that of Charles Simeon, the great leader of the 18th-century evangelical revival.

Although a close friend of, and collaborator with, the American evangelist Billy Graham, he indulged in no histrionics; and the emotional content of his message was balanced by the intellectual demands he made on his (mainly middle-class) audiences.

Stott's influence was greatly extended through his commitment to writing. He was the author of around 50 books, some of them Bible commentaries, others dealing with basic elements in Christianity, and all capable of being read with profit by both clergy and laity. These achieved enormous sales in paperback editions, and in some quarters were accorded an authority scarcely beneath that of the Bible. Virtually all of his considerable royalties went to charitable trusts.

The attribution of infallibility by some of his followers led those who were unsympathetic to his cause to describe him as the "Evangelical Pope"; but, while he was a man of the firmest convictions, he was imbued with deep humility and a strong pastoral sensitivity. Known to his flock as "Uncle John", he adopted a simple lifestyle: the Pembrokeshire cottage in which he did most of his writing had, until 2001, no electricity, only oil lamps.

John Robert Walmsley Stott was born in West Kensington, London, on April 27 1921. His father, Sir Arnold Stott, a distinguished physician of secularist outlook, soon took his family to live in Harley Street. (Family lore had it that John's first words were "coronary thrombosis".)

John's mother, who had been brought up a Lutheran, took her children to nearby All Souls church, where the future rector amused himself by dropping paper pellets from the gallery on to the heads of members of the respectable congregation below.

His leadership qualities were noted at Rugby, where he experienced an evangelical conversion, and he went as a scholar to Trinity College, Cambridge, to read Modern Languages with a view to entering the Diplomatic Service. By the time he had taken a First in French and a Second in German, however, he had come under stronger evangelical influences and stayed on to take a First in Theology.

Throughout his years at Cambridge, Stott was involved in an unhappy conflict with his father, who had served in the Great War and was now a major-general in the RAMC. Soon after the outbreak of war in 1939, John declared himself a pacifist, refusing to undertake any form of military service; his mortified father now strongly objected to his son's new ambition to seek Holy Orders. In the end, John was granted occupational exemption and father and son were reconciled.

After a year at Ridley Hall, Cambridge, in 1945 Stott was ordained to a curacy at his home parish church (then out of action owing to wartime bombing, with the congregation meeting at nearby St Peter's, Vere Street). He made an immediate impact with his preaching and pastoral work, and after four years he was given the choice of becoming a chaplain at Eton or taking on a parish in the East End.

In the event, he decided to stay on a little longer at All Souls, and in 1950, after the death of its much-loved rector, Harold Earnshaw Smith, the 29-year-old Stott was appointed his successor.

What Stott lacked in experience, he more than made up for in vision, dedication and skill. Soon the church - in need of major repairs and development - was being rebuilt. He believed that a local church should be a primary agency of evangelism, and that all its members should be involved.

Guest services were held for the uncommitted; overseas students were given special attention; there was a new ministry to professional groups such as doctors and lawyers; and chaplains were appointed to West End stores. The proximity of the BBC offered many broadcasting opportunities, which Stott enthusiastically took up.

Before long, there were attempts to entice him to undertake other work. In 1955 he was pressed to become principal of the London College of Divinity, in succession to Donald Coggan; and a year later he was asked to go to Australia as a coadjutor bishop in the strongly puritan archdiocese of Sydney.

Both invitations were declined, for by this time Stott was spending much time leading missions in British and American universities - although some questioned the usefulness of the neo-fundamentalist message for university audiences.

During his first 10 years as rector, Stott published five books; became a chaplain to the Queen; and, as an acknowledged leader of the Church's evangelical wing, was closely involved in the Scripture Union, the Inter-Varsity Fellowship and the Evangelical Alliance.

He was also chiefly responsible for the founding of the Church's Evangelical Council in 1960 and the Evangelical Fellowship of the Anglican Communion in the following year. Both these were concerned that the various reforms then being proposed in the Church should not betray Biblical principles and Reformation doctrine.

More significant than any of these organisations, however, was the Eclectics' Society - a group of young and able clergymen who were deeply influenced by Stott. By the mid-Sixties it had 17 linked groups in different parts of the country with a combined membership of more than 1,000.

They joined him in organising a National Evangelical Anglican Conference at Keele University in 1967, which was addressed by the Archbishop of Canterbury. It was repeated 10 years later at Nottingham University, drawing nearly 2,000 delegates.

It became apparent that the traditional fundamentalist approach to the Bible had been modified in the name of hermeneutics; there was a new concern for worship and the sacraments; and a radical approach to political and social questions. Most startling of all was the announcement by Stott that he and his colleagues no longer wished to be leaders of a sect but aimed to take evangelicalism into the mainstream of the Church of England, which is precisely what they did.

But Stott's own future now became uncertain. There was talk of his becoming Bishop of Manchester, but the Dean and Chapter took fright and nothing came of it. On the other hand, 25 years at All Souls was quite long enough for a man who also had heavy national and international responsibilities; so a temporary solution was found by appointing Michael Baughen (later Bishop of Chester) as vicar of the parish, leaving the rector greater freedom to travel and to write more books.

For a time this arrangement worked well, but Stott was gradually drawn more and more into international evangelicalism. In 1974 he played a leading role in the Congress on World Evangelisation in Lausanne, which set out the movement's beliefs and global aspirations in a famous "covenant". The next year he handed over All Souls entirely to Baughen, himself becoming rector emeritus and an honorary curate of the parish.

During the next decade he wrote 11 books, continued his travels and in 1982 founded the London Institute for Contemporary Christianity.

Stott was never prepared to compromise on the priority of Biblical revelation, and it was this unwillingness that stood in the way of his appointment to an English bishopric. At one time he let it be known that he would like to become a bishop in order to increase his influence and "the opportunities for preaching and defending the Gospel".

But when, in 1985, Archbishop Robert Runcie indicated privately his readiness to support Stott for the bishopric of Winchester, Stott begged to be excused, later saying: "I felt that I could not now change the whole direction of my ministry without acknowledging that I had made a mistake."

John Stott, who held six honorary doctorates and was appointed CBE in 2006, was an acknowledged authority on ornithology and a gifted photographer. He did not marry, having felt called by God to remain single. He died listening to Handel's Messiah.

END

The Guardian on the death of John Stott

Influential evangelist and founder of the Langham Partnership

by David Turner

www.guardian.co.uk

July 28, 2011

John Stott in 2006. He has been described as 'a renaissance man with a reformation theology'. Photograph: Kieran Dodds

John Stott in 2006. He has been described as 'a renaissance man with a reformation theology'. Photograph: Kieran Dodds

Though the name of the Rev John Stott, who has died at the age of 90, rarely appeared in the UK national press, in April 2005 Time Magazine placed him among the world's top 100 major influencers. A comment piece in the New York Times six months earlier had expressed surprise that he was ignored by the press, since he was a more authentic advocate for evangelical Christianity than more colourful figures such as Jerry Falwell.

Stott, radical in his conservatism, could not be pigeonholed. He was deeply committed to the need for social, economic and political justice and passionately concerned about climate change and ecological ethics. He regarded the Bible as his supreme authority and related its teaching to all areas of knowledge and experience. He insisted that Christians should engage in "double listening" - to the word of God, and to the world around them - and apply their biblical faith to all the pressing issues of contemporary culture. He himself researched, preached and wrote on a wide range of matters - from global debt to global warming, from the duties of the state to medical ethics and euthanasia. This was the kind of evangelicalism he embodied.

Stott was born in London, the fourth child and only son of Sir Arnold Stott and his wife, Lily. His father, a Harley Street physician, hoped he would enter the diplomatic service, and his peace-seeking spirit could have equipped him well for this. But at the age of 17, while at Rugby school, Warwickshire, his plans took a different turn. One February afternoon, he came to view the Christian gospel as compelling, and shortly afterwards resolved to be ordained into the church.

From school, having been excused national service as a conscientious objector - though he later came to accept the validity of the idea of a just war - Stott went to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he gained a double first in French and German. He then trained for ordination at Ridley Hall, Cambridge. In 1945 he became a curate at All Souls, Langham Place, in central London. This was the church where, as a child, he had terrorised the girls in Sunday school with his toy guns and daggers.

Stott has been described as "a renaissance man with a reformation theology". He had a sharp inter-disciplinary mind, and always worked to bring his thinking under the scrutiny of the Bible. It was, he believed, possible to understand the world only in the light of the Bible's teaching about God and humankind.

While the US evangelist Billy Graham, a long-time friend, was drawing tens of thousands to sports stadiums, Stott's mission field was the university campus. He conducted week-long events at universities in many countries, presenting a case for a Christian worldview, and drawing even the most cynical students into the pages of the New Testament.

In 1950, while only 29, he became rector of All Souls, a crown appointment. When released by the Church of England for wider ministry in 1970, he moved into a mews flat above the rectory garage. This modest two-roomed home became his base until 2007. Much of his substantial writing - a total of 50 books translated into 65 languages - was completed in a remote cottage on the Welsh coast which he bought in 1954. It was at that stage derelict, and for many years had no mains electricity. Stott's books included the million-selling Basic Christianity (1958), Christ the Controversialist (1970) and The Cross of Christ (1986). His final book, A Radical Disciple, "to say goodbye to his readers", was published last year.

Stott was behind the shaping of The Lausanne Covenant (1974), a significant statement of international co-operation in the cause of world evangilisation. He founded several evangelical initiatives in Britain, including the London Institute for Contemporary Christianity (1982) of which the sociologist and broadcaster Elaine Storkey later became director, succeeded by Mark Greene. Through his work with the university Christian Unions in the UK and overseas, he engaged with many of the sharpest up-and-coming Christian thinkers while they were still students.

His influence in the church has spread to more than 100 countries through his founding of Langham Partnership International. In the US, it operates under the name of John Stott Ministries. This threefold initiative, now under the direction of the theologian and author the Rev Chris Wright, works to strengthen the church in the developing world by training preachers, funding doctoral scholarships for the most able theological thinkers, and providing basic, low-cost libraries for pastors. Stott's own considerable royalties from his writing went towards the production and distribution of theological books in developing countries.

Stott was appointed CBE in 2006. He had served as chaplain to the Queen (1959-91) and then as extra chaplain until he died. His six doctorates included one from Lambeth Palace.

From childhood, Stott was taught by his father to love the natural world. He became an expert self-taught ornithologist, sighting and photographing some 2,500 bird species.

Urbane and gracious as both visionary and strategist, Stott left the Langham Partnership as perhaps his major legacy. His influence will doubtless attract much further attention.

* John Robert Walmsley Stott, clergyman and theologian, born 27 April 1921; died 27 July 2011