ANGLICAN FINANCIAL TRANSPARENCY: A LAMBETH CONFERENCE IMPERATIVE<.b>

By Benjamin M. Guyer, Guest Contributor

https://covenant.livingchurch.org/

June 30, 2022

"Charity rejoices in the truth."--1 Corinthians 13:6

An oft-named but otherwise shadowy presence haunts current Anglican difficulties: money. With most of the Communion living in the developing world, economic disparity defines an unknown number of relations between the Anglican provinces of the more affluent Global North and those of the far poorer Global South.

Although correlation is not causation, this financial gap strongly parallels other differences in the Communion. On both moral and theological matters, most liberal Anglicans live in prosperous countries, while Anglicans in developing nations are more conservative.

Demographic differences abound as well. Conservative churches in the developing world appear to be growing, while progressive churches in the developed world are consistently declining (for a broad survey, see here; https://covenant.livingchurch.org/2022/02/22/is-anglicanism-growing-or-dying-new-data/ for a more critical view of decline, with primary reference to the United States, see here; https://covenant.livingchurch.org/2021/12/20/alternative-facts-on-church-growth/

Consider the following. In 2007, The New York Times reported that the Episcopal Church provided "at least a third of the Communion's annual operations." The Communion then had 38 provinces comprising 77 million members; the Episcopal Church had 2.3 million members, meaning that just 2.98 percent of the Communion's membership controlled at least 33 percent of its wealth.

Let all who protest inequity take note. At a global level, financial disparity is even more stark. According to the World Bank, 11 countries in sub-Saharan Africa -- including Nigeria, which has a large number of Anglicans -- "saw stagnating or even declining wealth per capita between 1995 and 2018 as population growth outpaced net growth in asset values." Meanwhile, "the United States holds the largest share of global wealth in 2018, at 25 percent" (see the full World Bank report here, p. 88). Again, let all who protest inequity take note.

Treating St. Paul's words on charity as a polyvalent exhortation to both Christian virtue and Christian benevolence, this essay argues that the Anglican Communion needs to embrace financial transparency in order to counter the weaponization of wealth across its provinces. In what follows, I first call the unscrupulous use of money simony. In order to show how profound a problem Anglican simony is, I then chronicle at some length more than two decades' worth of mutual accusations of financial manipulation. I was surprised by the sheer volume of what I discovered in my research, and thus include it here. My conclusion sketches a constructive proposal for the future. Money is power and power is a dangerous thing. We need controls upon such power to prevent its abuse.

I. What Is Simony?

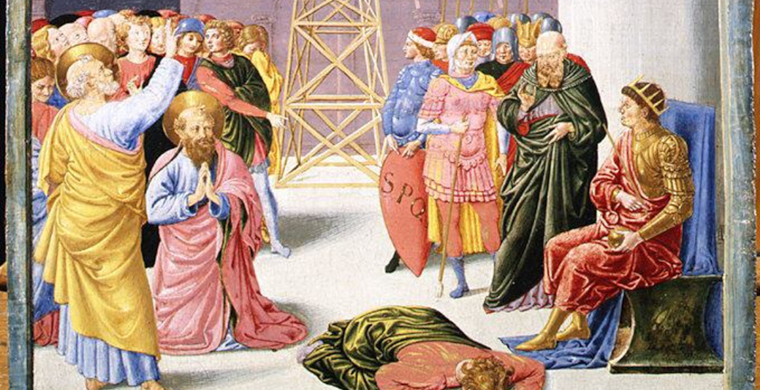

"Simony" is an old word, and likely unfamiliar to many. It denotes the use of financial and possibly other material inducements to gain either ecclesial office or influence within the church. The term "simony" comes from Simon Magus, a sorcerer who offered the apostles money for miraculous power (Acts 8:9-24). The story culminates with the following scene.

Peter said to him, "May your silver perish with you, because you thought you could obtain God's gift with money! You have no part or share in this, for your heart is not right before God. Repent therefore of this wickedness of yours, and pray to the Lord that, if possible, the intent of your heart may be forgiven you. For I see that you are in the gall of bitterness and the chains of wickedness." Simon answered, "Pray for me to the Lord, that nothing of what you have said may happen to me." (vv. 20-24)

Over the course of Christian history, all kinds of figures have inveighed against the sin of simony, from ecumenical councils to medieval heretics, from devout saints to the more acerbic of early Protestants. The reason ought to be obvious. To borrow from St. Paul, "the love of money is the root of all kinds of evil" (1 Tim. 6:10). Simony brings evil into the Church.

II. Accusations of Simony: 20 Years and Counting

Accusations of financial manipulation are not recent. In fact, they predate the American Episcopal Church's controversial ordination of Gene Robinson in 2003 as its first non-celibate gay bishop. In 2001, The Washington Times published a story detailing alleged instances of the Episcopal Church terminating funding, for ideological reasons, to Anglican churches in the developing world. Soon after Robinson's elevation, The Washington Post included an allegation by Archbishop Bernard Malango, the primate of Central Africa, who claimed that Trinity Church Wall Street cut off grants to his province due to the latter's conservatism. Trinity Church Wall Street denied the accusation, countering that Malango was the guilty party, and that conflicting stances on gay marriage were unrelated to the decision.

Questionable financial decisions are not restricted to progressives. In 2005, Robin Eames, Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of Ireland, publicly stated that he was "quite certain" that conservative Episcopalians in the United States were using financial inducements to align themselves with conservative Anglicans in the developing world. Peter Akinola, Archbishop of Abuja and Primate of Nigeria, responded to Eames in a public letter that challenged the Irish prelate to bring forth evidence. Akinola wrote that it was "uncharitable and untrue" to claim that Anglicans in the Global South had been "bought." Notably, Eames never produced any evidence to support his contention (and how he would have secured such evidence is unknown). However, Akinola also never denied that Anglicans in the Global South had received financial or other assistance from North American conservatives. In a follow-up statement, Eames backed off of his accusation, but restated his concerns of conservative financial influence.

Subsequent events revealed that conservatives were far from innocent -- and that, in fact, ideology and economics were long since intertwined. In 2000, Rwanda was one of two Anglican provinces that sponsored the creation of the Anglican Mission in America (AMiA), which attempted to create a new denomination of conservative Anglican churches in North America, partially under Rwandan episcopal oversight. But after barely a decade, the relationship soured between the AMiA and the Rwandan church. Through a large document dump on the website Scribd, it was revealed the AMiA had a generous financial relationship with the Church in Rwanda and had given millions of dollars to the African church. In 2011, an argument broke out over whether the AMiA had given its annual gift; it claimed that it had done so, the Rwandan bishops claimed that it had not, and they threatened to excommunicate the AMiA unless it paid.

Perhaps ironically, Onesphore Rwaje, the Archbishop of Rwanda, called for the AMiA to embrace financial transparency by sharing its financial records with the Rwandan bishops. The AMiA refused to do so, and mutual accusations of financial deception followed. Archbishop Rwaje was subsequently accused of trying to extort a quarter of a million dollars for personal use from the AMiA, a charge that he denied. The Rwandan bishops sided with their archbishop and the AMiA fractured. Most of its churches changed their denominational affiliation and joined the Anglican Church in North America (a new African-affiliated initiative in North America). Today, the AMiA has largely ceased to exist. Once a denomination of more than 200 churches, it now contains barely two dozen, and what little remains is no longer affiliated with the Anglican province of Rwanda.

Matters have only intensified since then. In 2013, the Global Fellowship of Confessing Anglicans (then GFCA, now GAFCON), a conservative movement based in the Global South, began soliciting financial contributions from across the Anglican Communion. As they wrote in their 2013 Nairobi Communique,

We ... invite provinces, dioceses, mission agencies, local congregations and individuals formally to become contributing members of the GFCA. In particular, we ask provinces to reconsider their support for those Anglican structures that are used to undermine biblical faithfulness and contribute instead, or additionally, to the financing of the GFCA's on-going needs.

Between the AMiA's 2011 implosion and GAFCON's 2013 appeal, there is no denying that financial incentives have become increasingly central to the larger state of international Anglican fracture and realignment.

But conservatives are not unique here. The Episcopal Church has responded to all of this in a regrettably tit-for-tat fashion. Expecting the Lambeth Conference in 2020 (thus, before its rescheduling due to the COVID-19 pandemic), Gay Jennings, President of the Episcopal Church's House of Deputies, publicly stated in 2019 that, "I think that the day is coming when we will need to take a hard look at where and how we invest the resources of The Episcopal Church across the Anglican Communion." Similar views were soon found on social media. As Lee Curtis, an American Episcopal priest, wrote on Twitter:

In fact, the Episcopal Church has been quietly decreasing its financial contributions to the Anglican Communion Office since at least 2015. But with President Jennings's words, it is now fully clear that for at least some American Episcopalians, communion comes with a price -- a price that they alone determine. Let all who protest inequity take note.

III. A Proposal

Two problems arise from the foregoing. First, Akinola's response to Eames in 2005 is less clear-cut than it might seem; poorer Anglicans can -- presumably -- receive aid without being "bought" (to use Akinola's phrasing). But does the conflation of charity with ideology fundamentally pervert the former, rendering it a form of manipulation? The epigraph of this essay, "Charity rejoices in the truth," could be glossed as, "Charity rejoices in transparency." Because transparency facilitates accountability, and accountability facilitates honesty, the burden of proof is upon those who deny the need for financial openness within the Communion. In truth, charity is only charity when there is nothing else at stake.

Second, at this point in the Communion's history, questionable financial relations already exist, and it would be wrong to abrogate them. Whatever their origins, such relations help mitigate sometimes acute humanitarian need. Western funds are used for things such as water purification and primary education in the developing world. Consider Rwanda Ministry Partners (RMP), which "connect[s] people, churches, and organizations in North American with the Anglican Church in Rwanda." Evidence of their successes, which no one should denigrate, can be seen on their Facebook page. Four of the six members of RMP's Board of Directors are clergy in the ACNA; a fifth is an Anglican bishop in Rwanda (I cannot locate information on the sixth, a layman and RMP's treasurer). Suffice it to say that the work of RMP should not be halted. Rather, its financial base should simply be shifted.

The following three steps will help create a more financially transparent Communion:

1. Declaring Finances

Every province should make publicly available, on a searchable database centrally located at anglicancommunion.org, the following:

o Annual provincial budget

o Sources of money that fund the budget

o All financial gifts, including those both to and from the Anglican Communion Office and other Anglican provinces

A set format for these budgets, and a detailed list of any necessary additional categories for inclusion, can be determined in the future. But the only provinces who will balk at this will be those with something to hide.

2. Maintaining Support

Amidst beginning to practice financial transparency, the Communion should ensure that preexisting charitable commitments are maintained without interruption. Anglicans in developing nations should not fear losing access to the money that they depend on. Nonetheless, it behooves the Communion to define acceptable financial relations.

3. Developing a Financial Institution for the Communion

In mid-2013, Archbishop Welby proposed the creation of a Church of England credit union to help those in financial need. At the time, many if not most saw this in terms of social justice and the Christian commitment to the poor, but my first thought was, "This would be brilliant for wider Communion." Such an institution could become the hub for financial aid throughout the Communion and would facilitate the Communion's work with the wider world.

Charitable causes could be organized in the following way. Specific accounts would pay out to specific causes (e.g., Rwanda Ministry Partners), but anyone -- whether within or beyond the Communion -- could contribute to these same accounts. Donations could therefore come from provincial, diocesan, congregational, and/or individual sources. This would remove charity from the control of vested interests and transform it into a matter of shared Christian concern and commitment.

And let's be honest: expanding the potential donor base for these charities would likely help them meet and exceed their goals far more quickly. If the goal of these charities is in fact humanitarian, then there is no reason to argue against my suggestion here.

Conclusion

If we refuse to speak truthfully about our internal financial relations, how can we distinguish between acts of charity and acts of coercion? Might they not be one and the same? Accusations are borne of suspicion, and suspicion is nourished by secrecy. A financially transparent Anglican Communion may not be more righteous, but it will have fewer places where the more corrupt recesses of the heart might hide. Charity is only charity when there is nothing else at stake. And right now, everything else is at stake.

Dr. Benjamin Guyer is a lecturer in the department of history and philosophy at the University of Tennessee at Martin. His monograph How the English Reformation was Named: The Politics of History, 1400-1700 is forthcoming from Oxford University Press. He is the co-editor with Paul Avis of The Lambeth Conference: Theology, History, Polity and Purpose (Bloomsbury, 2017).