Should the Church generate a £1 billion fund for slavery reparations?

by Ian Paul

https://www.psephizo.com/

March 8, 2024

PR car-crashes for the Church of England are like buses--there are none for ages, then three come along at once. Except for the Church of England, the 'there are none for ages' bit isn't true.

Following the constant stream of negative publicity about the sexuality debates, we then had two reports on safeguarding, Wilkinson and Jay, with the latter simply setting us up to fail. Instead of being asked to look at options for independent safeguarding practice, and independent safeguarding scrutiny, Professor Jay was briefed to look only at the option of fully independent safeguarding practice, despite the fact that experts in this field think that is a very bad idea. So either we follow her recommendations and do something stupid, or we do something sensible and get accused of defying the recommendations of the report.

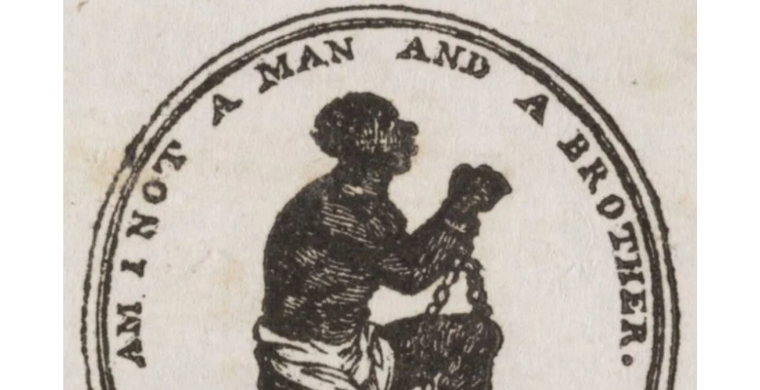

Something similar has now happened on the question of race and slavery reparations. The Church Commissioners wanted to investigate any past dependance on and profit from the transatlantic slave movements, and found that its predecessor, the Queen Anne's Bounty, had profited from investment in the South Sea Company which was involved in the transport of 34,000 slaves out of the approximately 12.5 million transported on about 35,000 transatlantic voyages. Its involvement in the slave trade ran from 1715 to 1739--a total of 24 years. It has been estimated that the profit to the Bounty amounted to around 3%, though subsequently its main sources of income were elsewhere until it was taken up into the Church Commissioners which were established in 1948.

But you wouldn't know any of that from the report of the Oversight Group that the Commissioners set up to advise on the use of a £100m investment fund that had already committed to. Reading the report, you would get the impression that the historical chattel slave trade was the cause of all the world's racist ills, and that the Church of England was responsible for all of this.

The reasons for this are multifold, but they begin with the ignorance and distortion of both historic and present facts around the issue. The report claims:

African chattel enslavement was central to the growth of the British economy of the 18th and 19th centuries and the nation's wealth thereafter (p 5).

But this is not true. As Niall Gooch points out:

The typical discourse around these kind of proposals is endlessly frustrating. For example, it is often stated explicitly or assumed implicitly that British national prosperity was "built on slavery". This is flatly untrue: Britain was a wealthy country well before the transatlantic slave trade and continued to be one long after we had entirely banned slavery throughout the Empire, at no small cost to ourselves. Even at its height, slavery was a relatively small component of the British economy. The economic power that underpinned our time as global hegemon was largely the result not of dark deeds or plunder, but of our innovative, free and dynamic economy and political stability.

But there is an ironic twist to this: the wealth that came from the innovation of the industrial revolution came from the mining of coal and iron ore, gruelling work conducted by white working men, a group the Church of England continues to struggle to engage with. There are no quotas in place to measure the involvement of this racial group.

And the report fails to make any mention of the fact that slavery was a routine practice of tribal conflict within Africa itself, and was likely introduced into Europe through the slavery practices of Islam. All this can be found in any primer on slavery, such as Jeremy Black's Slavery: a new global history.

Whereas the prime European demand in the Americas was for male labour... in the case of these other trades[in the Islamic world] the demand was primarily for women, particularly as domestic servants and sex slaves. This was because there were few equivalents in the Islamic world to the large labour-hungry plantation economy of the European New World...Lack of sources makes it harder to estimate the number of Africans traded across the Sahara, the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean than across the Atlantic, but it was probably as many--and indeed there are suggestions that it was greater (pp 54--55).

And, on the other side of the historical argument, the report makes no mention of the significant role the Church of England had in the opposition to and abolition of the slave trade:

The Church's report and summary make no reference to Christians' admirable central role in the suppression and abolition of slavery. Anglicans (in addition to Quakers) were at the forefront of the abolition movement from the 1780s, all their bishops voted en bloc in favour when the abolition legislation was brought before parliament, and the Church spent considerable time, effort and expense for many years thereafter in suppressing the slave trade elsewhere.

The distortion of facts extends to the present, where it is claimed that Black Caribbeans are uniquely disadvantaged economically because of the structural racism in British society due to the legacy of the slave trade. But the very same ONS data points out that, in terms of the performance in education by racial group, at the top are Chinese, Asians, and then Black Africans, and at the bottom of the performance are Black Caribbeans and white working class--and in all groups boys perform worse than girls. (The chart on the right does not separate Black Africans from Black Caribbeans but does note the wide difference in other charts and in the narrative further up.) It is clear that the main factor here is not race; those groups performing well have cultures that value discipline and hard work and have an emphasis on family stability and marital commitment.

And the headline claim of the report, that the reparations fund ought to be not £100m but £1bn, is a figure that is simply plucked out of the air:

An overriding and consistent belief expressed by respondents was that £100 million is not enough, relative either to the scale of the Church Commissioners' endowment or to the scale of the moral sin and crime (p 7).

...which being translated means 'We asked some people, and they all through we should demand more'. That is no basis for a policy document--besides which, following such recommendations made on this basis would be illegal. The Commissioners, like the Archbishops' Council, is a charity and controlled by charity law, which requires that all decisions are made in the best interests of the charity on the basis of evidence. There is none in this report.

Why is the report so detached from reality on all its key points? Because it appears to be driven by the culture wars language of the United States, based on Critical Race Theory, which constructs and explains conflict in society by means of a Marxist binary between powerful white oppressors and oppressed black victims. This has found its way into theological thinking through the work of influential commentators like the late James Cone, who argues that Jesus was 'black' in the sense of being the ultimate victim of the 'white oppression' of the Roman Empire.

The definition of Jesus as black is crucial for christology if we believe in his continued presence today. Taking our clue from the historical Jesus who is pictured in the New Testament as the Oppressed One, what else, except blackness, could adequately tell us the meaning of his presence today? Any statement about Jesus today that fails to consider blackness as the decisive factor about this is a denial of the New Testament message. The life, death, and resurrection of Jesus reveal that he is the man for others, disclosing to them what is necessary for their liberation from oppression. If this is true, then Jesus Christ must be black so that blacks can know that their liberation is his liberation (from Black Theology and Black Power, 1970).

This seems to me to be an essentially racist configuration of both the world and Christian theology, taking as absolute racial categories in defiance of social and historical evidence, and overlaying that on Christian theology. It is no surprise then the report sees the entire global investment system as a white conspiracy which disadvantages black people at every turn.

But this distortion of theology also leads the group to make an astonishing call (in both the summary and in the full report):

THEOLOGY AND ETHICS

32. Penitence: We call for the Church of England to apologise publicly for denying that Black Africans are made in the image of God and for seeking to destroy diverse African traditional religious belief systems. This act of repair should intentionally facilitate ongoing and new sociological, historical and theological research into spiritual traditions in Africa and the diaspora, thereby enabling a fresh dialogue between African traditional belief systems and the Gospel. This work should reach beyond theological institutions and be presented in the enslaved to discover the varied belief systems and spiritual practices of their forebears and their efficacy. We recommend the Commissioners work with all faith-based communities to which descendants of African chattel enslavement belong.

The Church of England taking the gospel to Africa is apparently an act of Afriphobia (report, p 5) causing 'spiritual rupture' for which we should repent. So the whole reason for the Anglican Communion now being majority black (and Asian) is something we should regret! What on earth must African Anglicans think about this? The gospel, for which they are so grateful, and which they continue to share with great courage in the face of militant Islam, is something the Church of England regrets sharing with them? This demonstrates, more clearly than anything, the racist nature of this report, and the distance it has travelled from anything resembling orthodox Christian belief, let along Anglican doctrine.

And the 'welcome' given to this report by the Commissioners and the Archbishops appears to endorse this view.

All this was anticipated in 2022 by Charles Wide writing in The Critic:

In the wake of the 2020 Black Lives Matter demonstrations, the Archbishops of Canterbury and York felt they had to act. They had a golden opportunity to set in train an inclusive, broadly representative, generous, open-minded process to examine whether there are things about the structures of the Church, or the ways they are operated, which impede the Church's mission due to conscious or unconscious racism and, if there are, to propose effective remedies.

It would be motivated by love of God and neighbour, uninhibited by preconceived theories and categories. It would foster mutual understanding across the whole Church, as a widely-shared endeavour. Any proposals would be based on carefully gathered, objectively evaluated, contemporary empirical evidence. It would, by this, achieve a lasting, generally agreed settlement of this potentially explosive issue and avoid the bitter divisions which can be seen on the other side of the Atlantic.

The Archbishops could have done this. But they blew it.

Hurriedly, they set up an "Anti Racism Taskforce" which, as the Archbishop of York said, was "not intended to be a broad representation of different church contexts". Its starting point was the Archbishop of Canterbury's sweeping assertion that the Church is "deeply institutionally racist".

Hampered by Covid, the taskforce never physically met, had limited specialist expertise, conducted no critical analysis of work done (often many years ago) by the Committee for Minority Ethnic Anglican Concerns, commissioned no contemporary research, delegated topics to small groups of its members or even a single member, never considered the possibility of causes of disparity other than racism, and did not evaluate or conduct cost-benefit analysis of any of its 47 "actions", which are now treated as Holy Writ.

The work was then taken up by the Archbishops' Racial Justice Commission (ARJC). Its members were selected in secret, with no open competition, and no published criteria for appointment. It seems to believe that its role includes delivering the Taskforce's "actions", despite their manifest deficiencies. The ARJC has just produced its first report. Its institutional mindset is revealed by an otherwise unimportant detail: the adoption of the term "GMH". This neologism stands for "Global Majority Heritage" and means everyone in the world who is not white. It is an activist invention, spun out of divisive, dehumanising "critical/intersectional" theories, according to which society is crudely understood in terms of the exercise of power and categories of oppressor/oppressed.

Wide is highlighting a double dynamic here in terms of process. Like the previous report, From Lament to Action, this one avoids engaging with evidence, and completely disregards its actual brief; issues around governance, due process, and accountability have been completely set aside. And in both cases, the authors appear to have been egged on by people in positions of influence; I understand the that figure of £1bn was specifically suggested to them. This is more evidence of the incoherence of governance that is dogging the Church at every turn.

The reaction has been fairly predictable--across the spectrum of views, this is seen as a disaster. Niall Gooch notes:

Explicitly associating one ethnic group with systematic wickedness is deeply wrong and a recipe for unrest and antagonism. It is particularly grim coming from Christians, who ought to be in the business of promoting racial harmony, not crank theories about how all the problems of society are the fault of a certain group.

Alka Sehgal Cuthbert, director of campaign group Don't Divide Us, notes how widespread this problem is:

The church has been busy embedding critical race theory in virtually all of the bodies it runs. Its Diocesan Board of Education has produced CRT-infused teaching materials and guidance for schools. Complete with images of BLM-style raised fists, this guidance encourages schools to teach kids about 'white privilege', amplify 'black voices' and celebrate 'black history'.

It gets worse. At the General Synod's bi-annual conference last month, the church adopted a 'racial justice' motion. This passed with an overwhelming majority, with 364 members voting in favour and two abstaining. As a result, every parish in England has been told to create 'race action plans', which is code for yet more racial quotas and CRT training.

Jawad Iqbal points out that the Church is digging itself into a hole on this question, from which there is no way out.

Why should anyone else give money to the church's scheme for washing itself clean of its role in the slave trade? It is a pipe dream to think that the church authorities could justify contributing more funds at a time when so many parishes are struggling. The difficulties are compounded by reports that more than a year after the original £100 million fund was set up, it is still not operational.

Is anyone surprised? Moral grandstanding over slavery is all well and good but channelling financial compensation is no easy task. It requires transparency, accountability and independence.

And of course for those who endorse the approach of the report, this will never be enough. The need to atone for the appalling evils of the slave trade will, according to historian David 'take generations.' So apparently this financial proposal is just the beginning of something that will continue well beyond our lifetime.

Three years ago, this was anticipated as creating nothing but problems:

The Rev Marcus Walker, rector at Great St Bartholomew in the City of London, said: "I can't help thinking they are stoking up trouble where none need necessarily be found [by] hunting for controversy. Shouldn't they be focusing their minds on how to keep the Church of England alive right now?"

And Stephen Glover expresses the anger that many feel about how this has been handled.

Slavery was an abominable evil, and one could certainly lose sleep contemplating man's inhumanity to man, while marvelling that the Anglican Church of 300 years ago should have briefly been the beneficiary of such a wicked business. But this reflection was not what kept me awake.

I thought of the failing, cash-strapped Church of England, which has closed more than 400 churches in the past decade because it couldn't afford to keep them open. As I tossed and turned, I also thought of impoverished vicars, expected to survive on an average salary of around £30,000 a year, admittedly plus free accommodation -- although these days that's far more likely to be a utilitarian box than a gracious rectory. I remembered the many poor people who, despite counting their pennies, give generously to the Church in the collection every week because that is what is asked of them.

And now it transpires that our weakened national Church, which can't or won't pay its priests a decent wage, and which has closed ¬hundreds of churches, hopes miraculously to lay its hands on £1 billion to atone for the sins of people who lived three centuries ago. Sins, moreover, that were visited on victims who are long dead and can no longer be helped in this world.

In amongst all this, there is an irony and a tragedy.

The irony is that the Commissioners have, for many years, been concerned about issues of justice and ethics in their investment policy. Their decisions on investment (along with other funds in the Church of England) are constrained by the stipulations of the Ethical Investment Advisory Group, of which I was a member for a time. As a result, they have become world-leading thinkers and practitioners on ethical investment, and exercise an influence in the world of investment far beyond the size of their fund.

But it seems that all counts for nothing, and is in real danger of being swept away by this ideological imposition.

And the tragedy is that the Church has all the resources it needs to address issues of race and injustice, yet the report sweeps those aside and even denigrates them. Those resources are found in the pages of Scripture, in the theology of creation that all are made in the image of God, and in particular in the New Testament and its astonishing, counter culture, and quite deliberate depiction of the people of God in Jesus as a diverse, multi-ethnic, and egalitarian community, most clearly expressed in the Book of Revelation:

After this I looked, and there before me was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, standing before the throne and in front of the Lamb. They were wearing white robes and were holding palm branches in their hands. And they cried out in a loud voice: "Salvation belongs to our God, who sits on the throne, and to the Lamb." (Rev 7.9--10)

As Scot McKnight notes (in Reading Romans Backwards):

Diversity shaped every moment of the Roman house churches, but Paul sought for a unity in the diversity, a sibling relationships in Christ that both transcended and affirmed one's ethnicity, gender, and status... Every person in each of the house churches in Rome had formed an identity apart from Christ and then in Christ, and the emphasis on 'in Christ' or 'in the Lord' in the names is as emphatic as it is often unobserved (pp 13--14).

The only way the Church of England is going to dig itself out of this race and slavery hole is by recovering its confidence in this vision. At the moment, all the signs are its leadership have a long way to go before that happens.

END