Recognizing Anglican Church Plants

By Vinay Samuel and Chris Sugden

http://anglicanmainstream.org/

June 4, 2015

John Wesley left two important legacies (among others) to the Anglican Church which he never left.

The first was religious voluntarism -- that Christian witness and fellowship could be carried out by voluntary groups within the wider church, not only by formal church structures. This was the basis of the 'group meeting' within Methodism, and the development of missionary societies in the Anglican church, such as CMS.

Methodist Group meetings were self-managed, self-propagating and therefore eventually self-governing. They were seen to reflect the New Testament model of the church.

The point of religious voluntarism was that people could respond to the leading and guidance of the Holy Spirit to carry out Christian mission and service without being formally established by the church hierarchy. They looked for validation and recognition not from the bishops, but from other believers. At the start of CMS no bishops would ordain people to serve with CMS so CMS began with pastors from Germany.

The second legacy flows from the first -- that of mutuality. The 'group meeting' existed not only for the support of individual members of the group but also to serve and support people outside its membership, especially the vulnerable. This task could not be undertaken alone but depended on a community of welcome and friendship. This is turn led to the development of mutual societies, building societies, the co-operative movement, trades unions and the Labour Party.

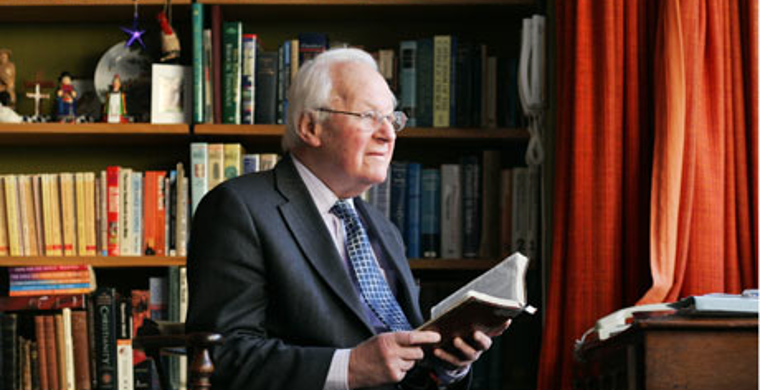

Both these concepts have profoundly affected the life of evangelicals in the Church of England through the tradition of Charles Simeon, John Stott (a founder of voluntary organisations in the church -- CEEC, EFAC, Langham Trust) and others. Evangelicals have not like others in the Church of England looked solely to the episcopal hierarchy for their validation. It was true that in the post-war period it mattered more to evangelicals that a view or course of action was approved by John Stott than that it was approved by any bishop. This however did not spring from an anti-episcopal stance. It had had roots going back to Wesley. And John Stott's approach was far from hierarchical. He placed himself and his hearers under the authority of scripture which all accepted.

And here lies a difference. One church tradition seeks primary validation and recognition from a hierarchy with impeccable traditions. The struggle over women bishops for those in this tradition was whether women could meet the criteria of that tradition and thus be acceptable validators.

Evangelicals have never been over worried about bishops -- except when they espouse heterodox doctrines and practices, for example their protests over David Jenkins and Jeffrey John. A hierarchy that sees itself as the prime source of legitimacy is based on position and power. The question that evangelicals ask is whether the person in the hierarchy has themselves conformed to received biblical teaching. The problem they find with bishops whose innovative beliefs go far beyond the bounds of Anglican orthodoxy is that they privilege their own knowledge and experience above the tested knowledge and experience of the church over the centuries. They assert their personal power over their received responsibilities. Such arrogance is properly resisted.

Evangelicals' conservative spirit is part of a culture which treasures things that have worked in the past. While they are open to changes for the future, they do not look to any hierarchy or powerful group to achieve that. They rightly suspect that the change proposed by any powerful group would benefit no one else but that group.

Evangelicals learnt to create a space for themselves in the Church of England by a process of mutual recognition of their voluntary societies. They would note if someone was 'sound'. They would recognize in each other faithfulness to the scriptures, obedience to the leading of the Spirit, a concern to win others for Christ, a reverence for the atoning sacrifice of Christ on the cross and a firm belief in the historic resurrection. These often found concrete expression in 'statements of faith'. These were a process of mutual recognition from below, not by a hierarchy from above.

Evangelicals are also committed to sharing the faith, to evangelism. This is not primarily personal witness but the expression of mutuality, a mutual enterprise. The Methodists and Plymouth brethren all fostered enterprises. Enterprise for the gospel is part of evangelical DNA. Such enterprise culture rarely, if ever waits for permission from hierarchies before launching into church planting. Such an enterprise approach is also the basis of its success.

These observations are relevant to Anglican church planting. When is a church plant an Anglican church plant? One answer is when other Anglicans recognize it as such; when they recognize that members of the new church plant identify that they have been called to be part of the fellowship of Anglican churches, share its creeds, formularies and order. They also recognize that the church has been called not only to benefit its own membership but also through mutual support engage with the community within which it is set.

When Christian people with an Anglican identity in an area want to express their Christian witness, are they not to be applauded when they do not travel miles to an established Church of England congregation but set up one in a school on a new estate because they know that if they travel away their witness to the community around will be the weaker? Far more effective will be a new community worshipping in a facility in the estate, visibly in the presence of and seeking to serve the wider community. Is this not Anglican witness at its best -- the church visible, and to be recognized as such?

This story also appeared in the Church of England Newspaper

END