Former archbishops split on assisted suicide, and there's no Anglican via media

Archbishop Cranmer Blog

September 13, 2021

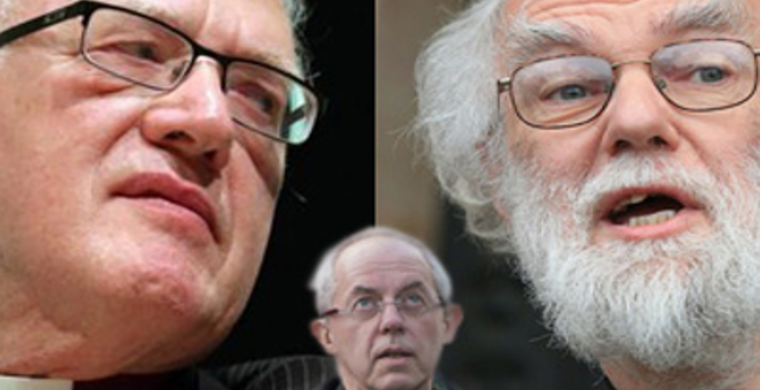

In the red corner is George, Lord Carey of Clifton, Archbishop of Canterbury 1991-2002. He favours the legalisation of assisted suicide (or assisted dying, if you prefer) because "there is nothing holy about agony". In the blue corner is Rowan, Lord Williams of Oystermouth, Archbishop of Canterbury 2002-2012. He opposes assisted suicide (or assisted dying, if you prefer) because of "the unacceptably high price of a change in the law".

There is no good old CofE via media between these two extremes: either the law permits assisted suicide, or the law prohibits it. If there were a middle way, Justin Welby (Archbishop of Canterbury 2012-today) would have found it. But he is firmly in the blue corner: he opposes assisted suicide (or assisted dying, if you prefer) because "a change in the law to permit assisted suicide would cross a fundamental legal and ethical Rubicon".

The arguments are well known and well-rehearsed: it is essentially a choice between human autonomy and the sanctity of life, with both sides claiming human compassion, societal virtue and clinical obligation. What is wrong with the 'right to death', Lord Carey might ask, provided that we protect the vulnerable with safeguards and judicial oversight?

And Lord Williams might respond that we can never protect all of the vulnerable because we can never know all the pressures to which they are subject, especially "from overstrained families as well as overstretched medical systems". This is a compassionate concern also articulated by Justin Welby:

Once a law permitting assisted suicide is in place there can be no effective safeguard against this worry, never mind the much more insidious pressure that could come from a very small minority of unsupportive relatives who wish not to be burdened.

The exhaustion of caring, sometimes combined with relationships that have been difficult for years before someone fell ill, can lead people to want and feel things that they should not. All of us who have been involved in pastoral care and bereavement care have heard the confusion people feel about how they behaved to a demanding relative. The tests in the bill do not make space, and never could, for the infinite complexity of motives and desires that human beings feel. The law at present does make that space, and yet calls us to be the best we can.

But what kind of God seeks to prolong the agony and indignity of human suffering? We already intervene at the beginning of life to the point of creating it test tubes, so why not intervene at the end to avoid "bodies sprouting a forest of tubes"? If there is "nothing in the scripture directly prohibits assisting a death to end suffering", why may it not be permitted? If the statistics are to be believed, the public (and the pews) are already there:

A massive change is going on in religious attitudes to assisted dying (by which a person is given a prescription for life ending drugs, which they themselves then order and take). Not least the fact that most church goers are in favour of assisted dying; a 2019 poll, for example, found that 84% of the British public, 82% of Christians, and about 80% of religious people overall supported assisted dying for terminally ill, mentally competent adults.

Those who oppose assisted suicide adduce their scriptures:

One of the very first passages contain within the Jewish prayer book, to be said each day upon waking, is: "God, the life-force you placed within me is pure; you created it, formed it, and breathed it into me. One day you will take it from me. As long as this life-force is within me, I will thank you." Every comprehensive Jewish prayer book also contains the ancient oral Jewish teaching that "against your will you are born, against your will you live, and against your will you die."

And those who favour assisted suicide adduce theirs:

Far from being modern, the problem of having to endure a painful end to your life has long been recognised in religious circles. The Book of Ecclesiasticus, for example, which is accepted in the Roman Catholic canon and is non-canonical but esteemed for Jewish and Protestant people, even expresses the view that "Death is better than a miserable life, and eternal rest than chronic sickness" (30:17).

There is no via media: Lord Carey is not persuaded by Lord Williams, and Lord Williams is not persuaded by Lord Carey. And Justin Welby is not a pope: there is no ex cathedra pronouncement to draw (or shunt) both sides together; no absolute moral teaching about whether the time to die is pre-ordained and reserved exclusively to God, or whether it may be a personal decision effected or facilitated by others. If 'the Lord gave, and the Lord hath taken away' (Job 1:21), has been usurped at the 'giving' with IVF and heart transplants, why can it not also be usurped at the 'taking away' with a cocktail of lethal drugs?

We can argue until the great and fearful day of the Lord, but the sanctity of life hath no fellowship with the sanctity of suffering; one is darkness, the other is light. Each side will make their impassioned case and find their reverberative soundbites, and both will adduce God, love, care, compassion and statistics to their cause.

And there is no pope to pronounce, and no via media to fudge.

Isn't it reassuring that in all the murkiness and messiness of life; in all the theological disputes over ethics and what it means to be human; in all the divisions over secondary doctrine and disunity around morality; and in all the arguments about confessional identity, ecclesial validity and episcopal authenticity, that there is a place for robust and very public argument in the Church of England, and that these disagreements don't result in excommunicative polemics or dust-shaking anathemas, but rather the visible community persists, and those within who disagree robustly carry on healing and converting to the fullness of communion.

The bonds of episcopal counsel which unite Anglicans all over the world may be a weakness of the Communion because that counsel is not always common -- even within a diocese, let alone a province -- but the commitment to mutual loyalty and fellowship is manifest. People may deride the spiritual fragmentation and confusion, or scorn the theological corruption and lack of moral clarity, but such is the nature of synodical government and conciliar ecclesiology; and such is the nature of humanity.

When all voices are heard, as they invariably are in the Church of England -- some meekly and hesitantly; others arrogantly and dogmatically -- there is something distinctive which emerges from the representative dialogue; something messier certainly, and yet something more reassuring. You may long for a more authoritative and definitive voice, but you can easily find that elsewhere. And when you discover it elsewhere, you may find yourself longing for something less authoritarian and more tolerant of your personal moral worldview and your chosen ethical nuances, because that which is agreeable to the Word of God is sometimes imprecise and mysterious, if not baffling and disconcerting.

In the words of David, Lord Hope of Thornes, Archbishop of York 1995-2005: "There is a holy reticence in Anglicanism's soul which can be tantalising, not only for those on the inside. But it can cut through doctrinal and moral controversy by recourse to paradox, and (on occasion) the humility to suspend judgment.'

The central truths of the Christian faith are affirmed in the Church of England, but Anglicanism is a practical and lived faith in a confused and sometimes bewildering world. You may despair at the limitations of its ecclesiology; that you can find a bishop or an archbishop or another member of its clergy whose pronouncements may be adduced to affirm your holy moral worldview, while any heretic can also find a bishop or an archbishop or another member of its clergy whose pronouncements may be adduced to affirm their depraved immoral worldview, but it is an undoubted strength that we rely on mutual loyalty, respect and gratitude rather than spiritual coercion or episcopal intimidation. This is not repugnant to the Word of God.

But, just to be clear, on the matter of assisted suicide (or assisted dying, if you prefer), Lord Carey is absolutely misguided and utterly wrong.

Just to be absolutely clear.