Christianity Offers No Answers About the Coronavirus. It's Not Supposed To

By N.T. Wright

TIME Magazine

March 29, 2020

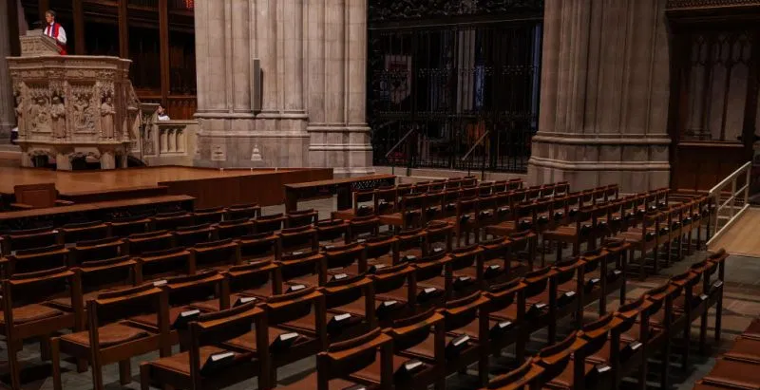

For many Christians, the coronavirus-induced limitations on life have arrived at the same time as Lent, the traditional season of doing without. But the sharp new regulations--no theater, schools shutting, virtual house arrest for us over-70s--make a mockery of our little Lenten disciplines. Doing without whiskey, or chocolate, is child's play compared with not seeing friends or grandchildren, or going to the pub, the library or church.

There is a reason we normally try to meet in the flesh. There is a reason solitary confinement is such a severe punishment. And this Lent has no fixed Easter to look forward to. We can't tick off the days. This is a stillness, not of rest, but of poised, anxious sorrow.

No doubt the usual silly suspects will tell us why God is doing this to us. A punishment? A warning? A sign? These are knee-jerk would-be Christian reactions in a culture which, generations back, embraced rationalism: everything must have an explanation. But supposing it doesn't? Supposing real human wisdom doesn't mean being able to string together some dodgy speculations and say, "So that's all right then?" What if, after all, there are moments such as T. S. Eliot recognized in the early 1940s, when the only advice is to wait without hope, because we'd be hoping for the wrong thing?

Rationalists (including Christian rationalists) want explanations; Romantics (including Christian romantics) want to be given a sigh of relief. But perhaps what we need more than either is to recover the biblical tradition of lament. Lament is what happens when people ask, "Why?" and don't get an answer. It's where we get to when we move beyond our self-centered worry about our sins and failings and look more broadly at the suffering of the world. It's bad enough facing a pandemic in New York City or London. What about a crowded refugee camp on a Greek island? What about Gaza? Or South Sudan?

At this point the Psalms, the Bible's own hymnbook, come back into their own, just when some churches seem to have given them up. "Be gracious to me, Lord," prays the sixth Psalm, "for I am languishing; O Lord, heal me, for my bones are shaking with terror." "Why do you stand far off, O Lord?" asks the 10th Psalm plaintively. "Why do you hide yourself in time of trouble?" And so it goes on: "How long, O Lord? Will you forget me forever?" (Psalm 13). And, all the more terrifying because Jesus himself quoted it in his agony on the cross, "My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?" (Psalm 22).

Yes, these poems often come out into the light by the end, with a fresh sense of God's presence and hope, not to explain the trouble but to provide reassurance within it. But sometimes they go the other way. Psalm 89 starts off by celebrating God's goodness and promises, and then suddenly switches and declares that it's all gone horribly wrong. And Psalm 88 starts in misery and ends in darkness: "You have caused friend and neighbor to shun me; my companions are in darkness." A word for our self-isolated times.

The point of lament, woven thus into the fabric of the biblical tradition, is not just that it's an outlet for our frustration, sorrow, loneliness and sheer inability to understand what is happening or why. The mystery of the biblical story is that God also laments. Some Christians like to think of God as above all that, knowing everything, in charge of everything, calm and unaffected by the troubles in his world. That's not the picture we get in the Bible.

God was grieved to his heart, Genesis declares, over the violent wickedness of his human creatures. He was devastated when his own bride, the people of Israel, turned away from him. And when God came back to his people in person--the story of Jesus is meaningless unless that's what it's about--he wept at the tomb of his friend. St. Paul speaks of the Holy Spirit "groaning" within us, as we ourselves groan within the pain of the whole creation. The ancient doctrine of the Trinity teaches us to recognize the One God in the tears of Jesus and the anguish of the Spirit.

It is no part of the Christian vocation, then, to be able to explain what's happening and why. In fact, it is part of the Christian vocation not to be able to explain--and to lament instead. As the Spirit laments within us, so we become, even in our self-isolation, small shrines where the presence and healing love of God can dwell. And out of that there can emerge new possibilities, new acts of kindness, new scientific understanding, new hope. New wisdom for our leaders? Now there's a thought.

A RESPONSE TO N.T. WRIGHT

NT Wright Is Wrong: Hope in a Time of Pandemic

By Owen Strachan

REFORMA

https://www.reformandamin.org/

April 1, 2020

N. T. Wright is known to many as a New Testament scholar of prodigious learning and a productive pen. Many evangelicals have major concerns over Wright's doctrine of justification but have also taken note of his helpful attention to the new heavens and new earth. Whether one agrees with Wright substantially or not, no one can deny that he is an estimable scholar.

For that reason, Wright's new TIME essay dealing with the Coronavirus pandemic surprised me and many others. It is entitled "Christianity Offers No Answers About the Coronavirus. It's Not Supposed To." In what follows, I want to engage four sections from the essay that call for further reflection, particularly as many people will read this TIME piece and think that several of its assertions reflect common Christian thinking. As we shall see, they do not.

First problematic assertion: Wright denies that "everything must have an explanation."

He writes:

No doubt the usual silly suspects will tell us why God is doing this to us. A punishment? A warning? A sign? These are knee-jerk would-be Christian reactions in a culture which, generations back, embraced rationalism: everything must have an explanation.

Here Wright seems to read evangelicals as claiming that Christianity offers a specific and immediately-accessible answer for crises. But most evangelicals I know do not think that we have the ability to offer people particular answers to their problems. Instead, from biblical teaching we are able to offer people general answers to the great questions of life. As one example, why God chooses to take a loved one long before we expect their death is a mystery to us, as we do not know the precise details of the plan the Father is bringing to perfect resolution in his Son (Ephesians 1:3-14). But though we may not know the particular contextual answer, we do know the general truth of such a tragic event: God is working all things for the good of those who love him (Romans 8:28).

Second problematic assertion: Wright argues that we should "wait without hope."

He writes:

What if, after all, there are moments such as T. S. Eliot recognized in the early 1940s, when the only advice is to wait without hope, because we'd be hoping for the wrong thing?

I confess that I find this a strange formulation. Granted, it's posed as a conditional question. Nonetheless the assertion here is that there are times when we "wait without hope." To see this come from the pen--the keyboard--of a professedly Christian theologian is odd (especially one who wrote a book entitled Surprised by Hope). We never "wait without hope" as believers. In any and all circumstances, we have sure hope and certain confidence, for we have believed in the Son of God who was crucified for our justification and raised three days later for our vindication.

This doesn't mean we should "hope for the wrong thing," of course. But being "without hope" and "hoping for the wrong thing" are not our only options. Instead, whatever comes our way in earthly circumstances, Coronavirus included, we can hope in God. We can do so because the resurrection--which Wright has devoted thousands of pages to!--is real. It's not only what happened to Jesus, it's what has proleptically happened to us. We are raised with Christ now, and thus shall be raised with him on the last day (see Colossians 3:1).

Third problematic assertion: Wright denies that God knows everything and is in charge of everything.

He writes:

The mystery of the biblical story is that God also laments. Some Christians like to think of God as above all that, knowing everything, in charge of everything, calm and unaffected by the troubles in his world. That's not the picture we get in the Bible.

This is one place in Wright's piece where I have partial and carefully qualified agreement with him. I do not affirm a theology of God where we understand him in light of our experience as much like us, just bigger. This violates the Creator-creature distinction, a hugely important theological principle (I've written about it here). But with that noted, I do affirm that the Lord chooses in his magnificent freedom to involve himself with our world, an involvement that is costly for him (rightly understood) as for us.

The Scripture gives us an impassible God but also an impassioned one, compassionately engaged with the travail and joy of his covenant people. This people is covered by the blood of the Christ who suffered terrible violence and felt wrenching pain and dereliction when he drank the wrath of God on the cross for us (see Matthew 26:39; Luke 22:20). There is real depth of experience here, real engagement with our world, and no abstract deity in the sky. (Here's a very careful resource on this difficult theological issue.)

Yet having noted this, I cannot help but register unchecked disagreement with Wright's disavowal of God "knowing everything" and being "in charge of everything." Here Wright sounds surprisingly like an open theist, the system of theology that argues that God's commitment to creaturely freedom leaves him unable to predetermine the cosmos. Wright seems to think that one is faced with one of two options: either one affirms that God's perfections dispose him to react him with love for humanity and displeasure with evil or one affirms that God is absolutely sovereign over creation. This is a false choice. In truth, we can affirm a version of both of these biblical realities. God is impassioned--in a divine way--against evil, for example, even as he ordains evil in order to bring his perfect plan of salvific love to pass.

If you do not embrace this second principle (and it seems Wright may not), then you truly do not have comfort or hope to offer anyone. If God does not know everything, then he definitely is not in charge. If he is not in charge, we are left in despair. This, of course, is not even close to a biblical doctrine of God. According to Scripture, God knows all things and omnipotently ordains all things (see Isaiah 45:1-7). He is in complete control of everything; not even a sparrow dies without his decreeing it (Matthew 10:29-31).

This extends to all facets of history, including the world's central event. As mentioned above, the Father planned and ordered the death of the Son who lived in the power of the Spirit (Ephesians 1:3-14). As we see from this text and others, the Godhead works at one purpose in accomplishing the glorious plan of redemption. All of time is playing out according to God's super-wise design, as the book of Revelation shows. The arc of history is long and the suffering of a fallen earth is great, but all things bend toward Christ, and all things resolve in Christ.

Fourth problematic assertion: Wright denies that Christians should even try to explain things.

He writes:

It is no part of the Christian vocation, then, to be able to explain what's happening and why. In fact, it is part of the Christian vocation not to be able to explain--and to lament instead.

In response we must note what we alluded to earlier: God's thoughts are infinitely above and beyond ours (Isaiah 55:8-9). Nonetheless, while we surely lack omniscience, we do not lack revelation. (Wright seems to conflate the two, a considerable mistake.) We do not possess particular knowledge of the immediate meaning of every event that plays out in our lives, no. But through the good gifts of doubt-dispelling special revelation and the Spirit who empowers us to trust God's Word, we do possess general knowledge of the character and plan of God.

This leaves us able, contra Wright's explanation of our non-explaining faith, to "explain" what is happening in this season of terrible global suffering. Of course, we do not unpack these glorious truths as dispassionate pundits. No, we weep with those who weep and mourn with those who mourn (Romans 12:15). There is indeed real reason to lament the suffering that is taking place in our world, suffering that owes to nothing good and traces back directly to the real historical fall of a real historical Adam (Genesis 3:1-13).

But while we lament suffering, we must also "give a reason for the hope that lies within" us (1 Peter 3:15). The word translated reason here, ἀπολογίαν in the Greek, can be translated "defense." (In similar terms, Paul says in Philippians 1:16 that he is appointed to give an ἀπολογίαν for the gospel.) Though Wright scoffs at what we could call biblical reason in his TIME article, Peter and Paul both tie the hope the church offers to the defensible truth found in Christ. This is what all Christians share; this is what pastors and elders, the church's leaders, must continually declare. Pastors are theologians, after all, whose very calling is to preach the Word--to expound it, explain it, apply it, and celebrate it (2 Timothy 4:2).

Conclusion

How striking that Wright speaks against both hope and rationality (in a biblical sense) in his essay. Truly, he ends up with neither; that is, we come away from his article neither gripped with the force of resurrection hope nor struck by the beauty of the true and defensible gospel of grace. Instead, we are left pondering that God laments evil and suffering, yet does so without fullness of knowledge or power.

This is nearly Easter season. Though I have many disagreements with Wright, some of them quite substantial, I would have expected an essay of his around this time of year to point to the subject he has written about so prolifically: the resurrection of Christ. The TIME op-ed does no such thing; it ends, oddly, on a political note.

Where Wright has missed his chance, I hope that many pastors will not miss theirs: I pray that this Easter (and every Sunday before and after it) the airwaves will ring out with the preaching of Christ crucified and raised for sinners like us. This is no exercise in puffed-up theology-splaining. This is the very calling of God's blood-washed people: to give a reason for the hope, the invincible hope borne of the triumph of Christ over the grave, that lies within us.