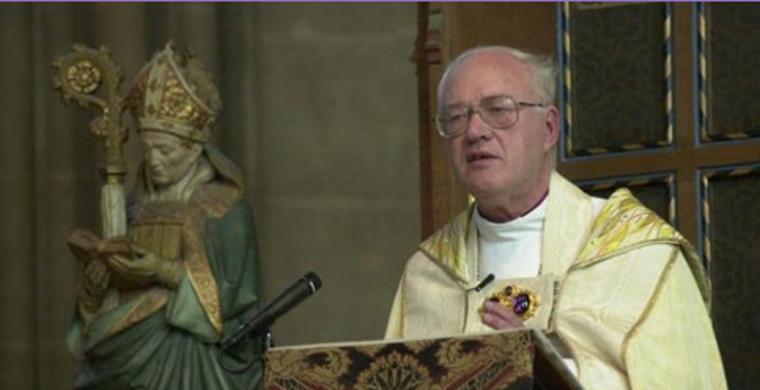

Lord Carey's forced resignation is an injustice: he, too, was a victim of Peter Ball

By Martin Sewell

http://archbishopcranmer.com/lord-carey-forced-resignation-injustice-victim-peter-ball/

July 4, 2017

This is a guest post by Martin Sewell, a retired Child Protection Lawyer and a member of General Synod. He considers here the wiles and manipulations of child-abuser Peter Ball, and advances a plausible defence of former Archbishop George, now Lord Carey.

If one reads the Gibb Report, with the child abuse story organised and catalogued in a single document, Lord Carey's serious errors and misjudgements are obvious, especially through the lenses of our modern understandings of abuse. Life is experienced in a much more haphazard and diffuse way, however, and the story evolved over a lengthy period. For substantial periods the name of Peter Ball fell off the agenda, and when he returned it is of the nature of everyday life that it was not always the case that 'joined-up thinking' resumed.

We also need to recall that Peter Ball operated in a period when it was seriously advanced on behalf of abusers of children that 'all children lie', that they did so for trivial advantage, and quite seriously by some psychiatrists, that all little girls fantasise about having sex with their fathers. These were times of a very different mindset, and Ball lived and operated in a church which simultaneously condemned gay orientation and acts, yet comprised of men like George Carey who felt compassion for their plight and vulnerability.

Like Jimmy Savile, Ball's professional reputation and successes within the Church conferred upon him a degree of untouchability which he knew, understood, and exploited. Like Savile, Ball worked within a large institution where many developed collective amnesia, willing to acknowledge 'rumours' but without a sufficient structurally rigorous safeguarding regime to collect all the evidence and force the key question to be asked: 'What does all this mean?'

The comparison with Savile needs to go a stage further.

Both he and Ball were able, by force of personality, to only to dominate their victims initially, but to hold them, isolate them and silence them beyond the time of direct influence. For many, it was only upon Savile's death that the spell was broken and they were finally able to tell those closest to them what had happened. We rarely speak of the power of evil in the modern world, but even the sceptical secularist struggles to explain such a phenomenon in any other way.

If you have never encountered such glib, plausible, manipulative abusers, it is almost impossible to fully grasp the way in which they successfully operate. It was especially rare for their brand of charismatic evil to be appreciated in the public sphere during the period when Ball was working on Carey.

The first point of defence is to note not simply how naive Carey was, but how many people were taken in -- not only by Carey, but Ball's own bishop brother who joined his brother to re-write the narrative. Carey had two of them working on him over a prolonged period of time exploiting an innate Christian kindness.

It was not only the Archbishop but nine further bishops who were ensnared, and countless others. Carey was being pressurised without independent advisors cataloguing the story, keeping him on the straight and narrow. The closer you let Peter Ball get to you, the less chance you had of seeing him for what he was. It is striking that it is mainly the remoter figures in the story, such as Deacon K, who actually got his measure at the time. Peter Ball's brother defended him from first to last.

Even some of Ball's victims spoke of the 'spiritual benefits' they experienced from his methods of distorting and corrupting spiritual exercise into abuse. He fooled a Lord of Appeal -- Lord Lloyd -- one of the most astute judges of his day, together with countless school headmasters, members of the gentry, and possibly members of the Royal Family. He persuaded a diocesan registrar to imprudently interpret the rule against conflict of interest in order to represent him in a personal capacity whilst simultaneously advising the church. These are not naive people, but all succumbed in various ways alongside George Carey.

If you want a model for Carey's ensnarement, think of the abused wife who is always making excuses for her abuser, or even Esther Rantzen, who was simultaneously setting up Childline and suppressing her doubts about Jimmy Savile as all the rumours reconfirmed everything she 'heard' but did not 'know'. Even now she honestly struggles to explain it. We used to convict wives who stabbed their abusive husbands because we reasoned that they could always walk away rather than resort to murder. Now we have a better understanding of the corrosive power of the emotional entrapment exercised by the manipulative abuser.

Once having 'got' Carey, Ball would have regarded him as a prize asset and not let him go.

There are two striking parts of the story that resonate from my own experience of such abusers.

First, Ball accepts a caution of gross indecency with a 17-year-old boy. That was plainly an offence at the time. Later he presents it as accepting a caution involving a 19-year-old, which would not have been a crime against a minor. That is clever and subtle. It refocuses the mischief from the plainly criminally abusive to the culturally unlucky. He implants the notion in a context where it may not matter enough for Carey to instantly go and check, and having re-ordered the narrative, Ball can then return and build upon its minimising implication at a later time. This is textbook manipulative behaviour, like a conjuror 'forcing' an idea or a choice upon a victim.

I do not make false equivalence between the Archbishop and his victims, whose abuse is infinitely deeper and longer lasting, but Carey is also a victim of Ball. Many of Ball's victims were persuaded to ignore what they thought and knew, and by the power of his charisma were induced to adopt and trust the narrative that has been implanted and developed.

Another familiar technique of the manipulator was his use of the Diocesan Registrar. Being close to his legal advisor, he might better hope to avoid receiving clear distanced advice of a challenging kind. He could build on the respect developed in happier times and thereby retain a measure of control. He gets the firm to mislead the CPS on detail about what is agreed, and they refer to a Royal reference which is never produced: it is easier to suggest that the church should 'pay the Diocesan Registrar' rather than 'pay my independent solicitor'. If the Diocesan Registrar is fighting his corner, the Church of England is also fighting his corner. Drip, drip, drip.

Later, when he decides the time is ripe to challenge the caution -- which he had been very lucky to receive -- he is happy to throw his solicitor under the bus, claiming that the Registrar was incompetent and let him down. Ball presents himself as the victim of advice he should never have accepted. Each step of the way he is exploiting the proximity, and rightly assumes that neither Carey nor anyone else will go back, read all the notes and remind themselves, reconnecting to the actual facts. Carey is only human. There is no computer to say 'No'.

This is classic behaviour which I have seen and encountered many times from such people.

He develops the tyranny of small concessions. You are hooked and weary, and just want to get on with other more important things. He wants to do confirmations? He tells you he's already done some, nothing went wrong, where's the harm? You can either go through it again or just give in because it probably doesn't matter, and he is a great inspirer of vocations and it was only a police caution: if it had been serious they would have prosecuted him over that 19-year-old... ( see what I did there?).

His brother Michael is a bishop who described his brother's behaviour as merely 'silly' and, according to the report, behaved in a way 'close to perverting the course of justice'. He tried to secure the status of an assistant bishop for his brother, petulantly declining one for himself if his brother were not similarly honoured.

Michael Ball has not suffered a penalty akin to that of George Carey, although his role in keeping Peter Ball within the church fold was crucial.

Archbishop Carey was ultimately responsible, but his brother bishops and the church structures of the time gave him scant help. Every institution of the time was making similar catastrophic judgements. Individualising the responsibility is not helpful because the very function of the scapegoat is to remove the sin from others. To coin a current phrase, the inadequacies from this time were of the many, not the few.

We must be careful to ensure that such reports continue to usefully inform us. George Carey co-operated with the Gibb Inquiry, and so, to his credit, did Bishop Michael Ball. These reports are improved by the frank and willing engagement of those who remember, though when there is delay, several of those who could have added perspective have died. They will include some who might have added to the indictment of George Carey, but also those who might have aided his defence. Justice delayed is indeed justice denied.

I offer the suggestion that it may be best for society if these kind of inquiries are regarded as more akin to the South African 'Truth and Reconciliation Commission'. Used in this way, we gain better insights and have a better chance of understanding how to avoid these problems in the future.

George Carey has been forced to resign. If he is now prosecuted, as some are now demanding, what message will that give future potential witnesses, and how might that distort our future ability to be informed and to learn? Pour encourager les autres has some coercive value, but it is not an obviously moral impulse when applied to a witness who has agreed to engage with his failures, only to find that his honesty paves the way to prosecution. We gain more from George Carey and Michael Ball testifying than from Peter Ball 'taking the Fifth Amendment'.

The Gibb Report is but the start of the problem from the Church of England's point of view. The Carlile Report into errors of the church in its handling of historical abuse in the case of Bishop George Bell will almost certainly add to our woes and the clamour for reform. The two reports deal with separate issues, but they have one thing in common: the current Bishops shaped the agenda. I say that as a structural point and in no way to personalise criticism of people doing their very best. That may not, of course, be enough in this context.

Very few in the Church want or wanted abuse to go undetected. That included George Carey.

The lesson that surely screams from the pages of the Gibb Report is that those who manage complaints must be much more professional, organised, and above all must not retain any personal connection with the person under consideration. The case for the out-placing of the investigations is becoming unanswerable. Unfortunately, if we direct our ire at the hapless Archbishop, we are almost certainly taking our eye off a much bigger picture.