Thinking About Augustine

By Duane W.H. Arnold, PhD

Special to Virtueonline

www.virtueonline.org

September 25, 2020

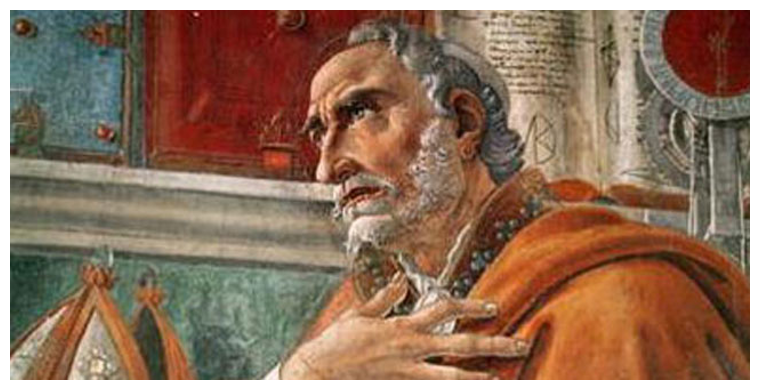

I’ve always considered Augustine to be a modern man. This is partly owing to his intellectual rigor, but also owing to the sweep of his life. Born about 354, he would live to the age of 76, dying in 430. Everything about him, from his split religious parentage (his mother was a Christian, his father a pagan) to his early life of ambition and sensuality, to his conversion, to his later writings, to his eventual elevation in the hierarchy of the Church, seems to mark him out as a contemporary figure. There is a sense that we can understand this life and this man. Even his work ethic seems modern. Initially a mediocre student, he discovered that he could make a name for himself through scholarship. In Carthage, at the age of 17, he devoured the classics (especially Cicero and Plotinus). He encountered Manichaean philosophy (a dualist corruption of Christianity) and became a teacher of rhetoric. Climbing the academic ladder, he moved first to Rome and then to Milan as the city’s leading professor, although now specializing in Neoplatonism, a system of philosophy embraced by both sophisticated Christians and pagans in the fourth century. He was, without doubt, “a man about town”. The influence of Ambrose, the Bishop of Milan, led to his well-known conversion. Yet even after his conversion, we can see ourselves in this man as he involves himself in lay communities of scholars and schemes to set up monastic establishments. His energy seems without end and all things appeared possible.

In 391, while in Hippo (where he was well known by reputation) he was ordained a priest. According to some stories, this was almost done against his will. Yet, within five years, he was made Bishop of Hippo. In his episcopate, we once again see a modern man. In addition to his pastoral duties within Hippo, he traveled to church councils in the region of North Africa – forty to fifty times over the course of the 35 years he served as bishop. He made the nine-day journey to Carthage, the metropolitan see, for meetings with other bishops some thirty times. But even these extensive travels, which Augustine always found to be a hardship physically, were modest in comparison with the great output of writings and sermons which he produced: over two hundred books and nearly a thousand sermons, letters and other works. It is no wonder, at least to me, that Calvin, Luther and Cranmer viewed Augustine as a theological contemporary, as did Warfield and Barth. There was, and is, the sense that Augustine can be known and understood in a modern and contemporary manner. Moreover, it does not matter if “modern” means the sixteenth or the twenty-first century. Indeed, in the great biography of Augustine by Peter Brown, there is evidence not merely of the “history” of Augustine’s life (i.e. dates and chronology) but also of his psychology and thought process documented in his extensive writings.

I would contend, however, that Augustine’s appeal to modernity arises not only from the life he lived, but also from the time in which he lived and how he responded to that time. His life and career began in an optimistic era in which a country boy from a small town in North Africa could make his way to Carthage and then to Rome and them to Milan. It was a time of relative peace and prosperity, both in the Latin West and in the Church. By the time of Augustine’s episcopate, however, the situation had changed. The Donatist controversy was splitting the Church in North Africa. Pelagianism had emerged and was dividing the faithful. Barbarian incursions took place in northern and central Italy and by 410 Alaric had breached the gates of Rome and sacked the city, resulting in an influx of refugees to Hippo, Carthage and the other cities of North Africa. It is reported that Augustine said that, “it seemed as though the world was on fire”. Yet, it is out of this time, this experience, that Augustine writes The City of God, telling his readers that we should not be astonished that the City of Man is bound to rise and fall. The task of the Church is not bound to that city made by earthly hands, but rather, “The whole of our history since the ascension of Jesus into heaven is concerned with one work only: the building and perfecting of the City of God”. We do this not by ignoring the City of Man, but by not aligning our destiny, or our hopes, with that earthly city.

Within 20 years the Vandals had made their way to North Africa. Augustine watched as all that he had systematically built over his lifetime was destroyed. As refugees from smaller towns fled to Hippo, they brought reports of churches being burned, monasteries being sacked, and of priests, monks and nuns being killed. As Hippo was a fortified town, the outlying fires could be seen from the walls of the city. As the Vandals arrived to lay siege to the city, Augustine updated and organized the library of his own writings. “So it falls out that in this world, in evil days like these, the Church walks onward like a wayfarer stricken by the world's hostility, but comforted by the mercy of God.” After three months of the siege, Augustine contracted a fever which likely was sweeping the town.

Apparently, he found this not to be surprising and reached back with his memory to the classics. As Peter Brown says, "In the midst of these evils, he was comforted by the saying of a certain wise man: ‘He is no great man who thinks it a great thing that sticks and stones should fall, and that men, who must die, should die. The 'certain wise man’ of course, is none other than Plotinus. Augustine, the Catholic bishop, will retire to his deathbed with these words of a proud pagan sage.” He remembered what he had taught decades earlier.

Augustine then took to his bed, hearing the sounds of battle outside, and prayed the penitential psalms which he asked to be written on the walls of his room. On 28 August 430, as Hippo was being sacked by the Vandals, Augustine died. Of his life’s work in North Africa, only his library miraculously survived.

Like Augustine, we cannot choose the times in which we live and I see many parallels between Augustine’s time and ours. We cannot heal the divisions in the Church which now seem insurmountable. We cannot quell the violence in our cities, much less the armed confrontations between nations. We have also wondered if the “whole world is on fire”. A pandemic claims 200,000 lives… the lives of our neighbors, and the best we can do it to argue politics, believing that the more we increased the volume, the more we will be heard. There can be little doubt that as a nation and as a society we are facing a seismic shift, for good or for ill. Navigating our way through this time requires wisdom which, unfortunately, seems in short supply. In the end, perhaps we recognize the limits of what we can do and loosen our grip on the earthly city that, “glories in itself”, for in the end, all we can do is act in the moment with love, which alone is the currency of the City of God. And if we want to know what that is about, Augustine provides a succinct definition:

“What does love look like? It has the hands to help others. It has the feet to hasten to the poor and needy. It has eyes to see misery and want. It has the ears to hear the sighs and sorrows of men. That is what love looks like.”

Duane W.H. Arnold, PhD

The Project