Interview with John Polkinghorne: Christ's resurrection -- and ours

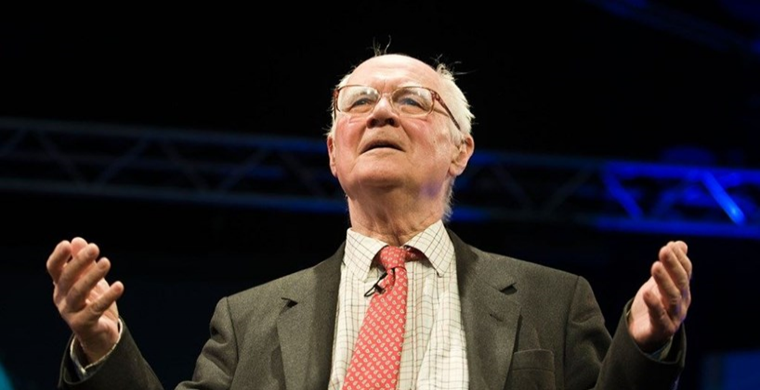

The eminent physicist, now 89, talks to Patrick Miles about life after death

https://www.churchtimes.co.uk/

April 9, 2020

Patrick Miles: Would it be true to say that the only empirical evidence we have for there being a life after death is the scriptural record of what Christ said about it?

John Polkinghorne: I don't think empirical is quite the word, because empirical implies that you can manipulate it, tie it to a board and take measurements, that sort of thing.

PM: I suppose, by empirical I mean the written word. The scriptural record of what Christ said about these things is documentary evidence, since he has authority. For instance, I think, perhaps, the reason a lot of people assume that they or their loved ones go straight to heaven is, of course, Christ's words on the cross to the penitent thief about being "in paradise with me today".

JP: Yes. This is a puzzle. It's well rehearsed in theological circles. I mean, "paradise" is a sort of garden -- it's a Persian word meaning "garden"; so I don't know what the best translation for it would be. I think essentially what Christ is saying is that what is good in you -- and your repentance shows there is a seed of that -- will not be thrown away.

PM: And, of course, what strikes everyone is that Christ said that the thief will be in paradise and not in hell, despite the thief being a sinner and all the rest of it.

JP: Yes, but "hell" is a tricky word. The original meant just "Hades", the abode of the dead, not a place of fire and torment.

PM: In his lifetime, on this earth, it seems to me that the one consistent thing about Christ's utterances concerning life after death is the phrase "eternal life". I mean, we have "paradise", we have "many mansions".

JP: These are all images, if you like, thought-experiments about what it may be like.

PM: But the most important concepts that Christ seems to use are "eternal life" and "resurrection".

JP: Incidentally, about "many mansions": that's a poor translation of the Greek. . . The original word might better be translated as caravanserai. So the picture is not one of a celestial hotel with everything laid on -- "This is your room!" -- but of a process. It means there are many "stages", and all these "stages" will be open to us.

People sometimes say that eternal life would be just boring: you know, sitting on a cloud and shouting "hallelujah", or something. But it is the unending exploration of the reality of God, progressively unveiled, that seems to me to be behind this image translated in the Authorised Version as "mansions". That seems to me the most persuasive picture of the life to come.

Resurrection or resuscitation?

PM: Another piece of "empirical" evidence that I think people take from the New Testament as evidence that there is life after death is incidents like the raising of Lazarus, or Jairus's daughter. But I remember when I was a teenager being mystified that there was no record of them describing their after-death experience. If they had really died, and been brought back to life by Christ, where had they been? They never said.

JP: It's very important to have a clear recognition here of the difference between resuscitation and resurrection. Resuscitation is the restoration of this sort of life. Lazarus and Jairus's daughter were restored to an active life, but not for ever. They were going to die again, and they did. But resurrection is the translation, through death, from this world to another world of reality . . . the world of the new creation.

PM: If these were resuscitations rather than resurrections, what was Christ intending to prove by them? His power?

JP: Certainly he was showing that, for God, nothing is impossible. But, just as important, they demonstrate Christ's humanity. He loved Lazarus and his sisters, and he was overwhelmed by compassion -- he wept. He felt complete solidarity with these humans in their grief, and his resuscitation of Lazarus was the expression of this.

PM: This is the mystery of Christ's resurrected form, isn't it? That he was not just resuscitated.

JP: Absolutely not, otherwise he would have had to die again. And that would have been the end of the story. So the resurrection is a transition from, if you like, life in the old world to life in the new world. And it's important not to confuse the two.

Evidence of Christ's resurrection

PM: The evidence for the resurrection of Christ, I think, is of a completely different order.

JP: Well, obviously, the resurrection of Christ, as I understand it, as Christians understand it, is that Christ is the "first fruits from the dead", the first sign. Whether or not to call that empirical is rather a sticky point. . . I mean, the one who wanted the empirical answer was Thomas. Thomas wanted to poke his hands into the wounds -- he said, "that's what I've got to do, no nonsense" -- that sort of thing. But, when Christ appeared to him, he didn't do that, he just fell at his feet and said, "My Lord and my God", which is actually the clearest assertion of a divine status of Jesus that you find in the New Testament.

PM: I find that almost unbearably moving.

JP: Absolutely. What we're trying to find is . . . a path between just saying "It's all, you know, comforting images," and that sort of thing, and that it has to have a reality to it.

PM: Of course, the presence of Christ resurrected was terrifying to the apostles in the first instance.

JP: I mean, something weird is happening here, and we wonder: what's going on? It's very striking, really, that the resurrection appearance -- and the empty tomb, too -- are not presented in a triumphalist sort of way in the New Testament at all.

PM: What I find strangely moving and authentic is that the Gospel-writers seem to have been so honest about it all. They didn't understand what was going on: it was odd, but they recorded it. They didn't try to explain it away. They even recorded that "some doubted".

JP: Yes, they don't make a great song and dance about it, really; it isn't a question of a hallelujah chorus and "this is the ultimate triumph of everything." When the women found the empty tomb, for example, it's fear they experience. And it isn't a question of people saying, "Oh, Jesus -- it's nice to see you back again!" and so on. In fact, they don't at first recognise him, which is presumably why "some doubted".

I think the way the stories are presented is convincing in the sense that they're not the immediately obvious thing that you might have made up if you just wanted to say "OK, the message goes on," or something like that.

Held in the divine memory

PM: When we were at school, the passage in Ezekiel about the valley of bones was taught to us as prefiguring the resurrection. But I read it again last week, and it seems that what you say about the Old Testament view of the soul applies: that these bones are reanimated.

JP: That's right: I think it's about resuscitation rather than resurrection. It's moving in the direction of resurrection, but they didn't get there all in one go. The general Hebrew tendency in the Old Testament was to see people as animated bodies rather than incarnated souls.

PM: Whereas we tend to think the other way round, don't we? That it is not our bodies that are animated but our souls that are embodied.

JP: Well, it's "the real me", and what that is is quite a complicated notion.

PM: As I understand it, it's difficult to say what the real me is, even physically. I mean, I may have got something wrong here, but, as I read you in Hope, most of the atoms in our bodies are replaced every two years?

JP: Yes, that's right.

PM: And yet we look the same, and even our scars and blemishes are the same.

JP: Yes, in my view this a good starting-point. We are convinced about the existence of the human person. You're a person, I'm a person, and, if that's the case, then there must be continuity in you in this world and a continuity in me, and that continuity at first sight appears to be simply material continuance.

But that, as I say, is an illusion, because, in fact, the atoms and so on are all changing all the time. And, therefore, the question is: what is the thing that remains the same? What is the thing that essentially is me in this world, and which might be the "me" of the soul, if you like, which God regards as his own? The answer must be -- and, of course, this is hand-waving, because we don't begin to understand how to say it, exactly -- that it's the pattern of these things rather than their mere existence.

PM: If this information pattern survives into death, what kind of information would it have?

JP: Of itself, it doesn't survive into death. It's a question of the memory of God. If the pattern has a continuance, if it has a significance, it will be held in God's memory. It's a bit like some great picture, a wonderful pattern, a picture. If you burn the picture, you've lost it, it's irrecoverable, then.

What I am saying is that a "pattern" is retained in some way, and I think the best image to use for that -- at least, the one most comfortable to me -- is of the divine memory.

PM: And, of course, this concept of the information-bearing pattern avoids the evolutionary problem with the soul, doesn't it?

JP: Yes. I mean, the soul is not some sort of "extra spiritual component" injected, or which evolves at some suitable stage -- you know, these questions like "At what stage does the soul arrive in the developing embryo?" and all that sort of thing. Those questions are missing the point.

PM: Is it a matter of continuance, of continuity, in the sense that he knows us now, he has always known us, and he will continue to know us?

JP: Yes.

Hope, belief, faith . . .

PM: Surely, if Christ was resurrected, there certainly is hope for us beyond death.

JP: I think most people have a sort of intuition of hope that, in the end, it does make sense; that, in the end, "All shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well," as Julian of Norwich says.

We use "hope" in two senses. One is a rather feeble sense of just expressing a wish: "I hope this marrow will win the prize", that sort of thing. That's a wish-list use of hope. What one's interested in, I think, is a stronger thing than that: that what is desirable in that sense will be brought about by some influence which is reliable -- which we can trust to bring it about. And I think that can only mean God, in some clear sense.

PM: Do you think, though, that that kind of hope really, at some point, becomes faith?

JP: Hope and faith are connected. Hope is the trust that there is, in this case, a God who can bring about a fulfilment. And that trust is, itself, faith: it is the commitment. Faith is not just a question of abstract knowledge. If faith is really trust dependent on the good will of a creator, it's something that will affect my life. I can't believe that Jesus was the son of God and was raised from the dead without it affecting my life. It isn't just a question of ticking the boxes: it is a question of how you orient your whole existence.

PM: Would I be right in saying that you believe that Jesus was raised from the dead because of the evidence?

JP: Well, of course belief has to be motivated. I don't think belief is just shutting your eyes and gritting your teeth. That's coming back to our weak sense of "hope". But, equally, I don't think you can believe that Christ was raised from the dead without it affecting your life. It isn't just the satisfaction of a curiosity. . .

To have a hope of a destiny beyond death is an indirect assertion of a belief in one who brings that about, who is faithful. I think many people have a true and lasting hope. Really true and lasting hope is not just a question of whistling in the dark for a while, it can only have its basis and its guarantee in the faithfulness of God, really. .

Reunion after death?

PM: It seems to me that in Hope you do not argue that after death we shall immediately go to a new life in the Spirit -- you offer people the certainty of resurrection at some indeterminate point in their future. Don't you think a lot of people concerned about a personal life after death will be disappointed to learn that it will be only "some form of re-embodiment"?

JP: We're thinking of the time of this world, and it's difficult to know how that relates to the time of the world to come. As I say, we might all arrive at the resurrection point at the same time, but it's not the time of this world.

I think it's important that the hope of ourselves is of a true, human survival, and that we are not spiritual beings -- ghostly beings -- who happen to have a body at the moment but that's a thing to get rid of.

It's important, absolutely intrinsic, to human beings that we are this strange sort of mixture of the spiritual and the material. Therefore, if we -- as ourselves, not as some sort of recollections or symbols or something -- are going to survive, it must involve a bodily existence of some kind.

PM: But when we actually die, do you believe we go to Christ?

JP: I think we are always with Christ in this world, too, but then we shall be in a more manifest way. We will know him, and we will know ourselves, as he knows us, which is part of what the process of creation is about.

PM: And will we know God?

JP: Well, yes! The point, however, is, of course, that God infinite is not fully known by human beings, and Jesus is the incarnate image of God. What is true of him is true of God, and he is our access to God, in that sense.

PM: I agree with you in Hope that the urgent question for most people is whether they will see their loved ones again. Your own reply is: "Yes -- nothing of good will be lost in the Lord." But might not your reply strike people as particularly illogical, given that you appear to reject "some kind of spiritual survival" after the death-event in favour of resurrection at some indeterminate future point?

JP: Well, I think it's not a question of seeing our loved ones again, it's the restoration -- or continuation -- of a relationship that you had with them. There will be some persisting relationship, and that is a good. I mean, one of the greatest goods of life in this world is our relationship to those who are near and dear to us, and that is a good that will not be lost, I think. It will be renewed and continued.

PM: In the Spirit?

JP: Well, as human beings. And, if we have to be embodied as human beings, as I believe we have, then it will involve that. Human relationships in this world are more than merely fleshly -- they have a different dimension to them.

PM: Do you think that most people, perhaps, think they will go straight to heaven when they die, or at least straight to the presence of their loved ones?

JP: This is a long-debated question, and there's been no theological agreement on it. In Reformation times, there was a frequent feeling that there must be what is called "soul sleep": a sort of anaesthetised period of waiting for the actual resurrection. I think the answer to that is, as to so many eschatological questions, "Wait and see.". . .

Patrick Miles is a Russianist and Senior Research Associate at Cambridge University. The Revd Professor John Polkinghorne was Professor of Mathematical Physics at Cambridge University. He is the author of more than 30 books, including The God of Hope and the End of the World (Yale University Press). Their conversation is recorded in What Can We Hope For? Dialogues about the future by John Polkinghorne and Patrick Miles, which is published by Sam&Sam (£5; 978-1-9999676-2-8; available from Amazon), and from which this is an edited extract.