LAMBETH AT 150 YEARS?

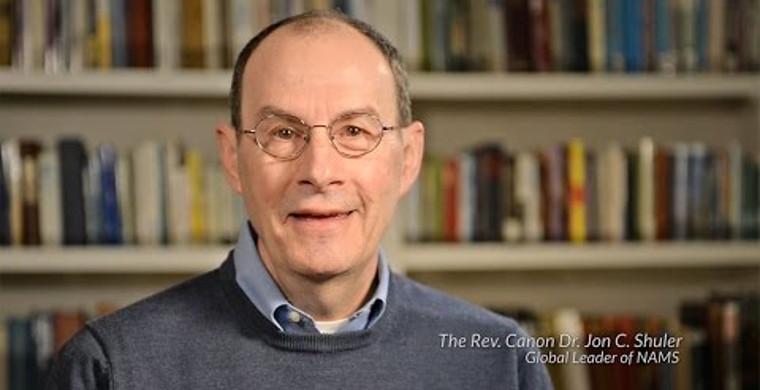

By Jon Shuler

www.virtueonline.org

Sept. 29, 2017

What if Archbishop Longley was wrong in 1867 when he wrote to all the Anglican Bish-ops? What if his caution (lack of courage?) in the face of open hostility in England to a General "Synod of the Bishops of the Anglican Church at home and abroad," allowed a fragile foundation to be laid that could not but break apart in the subsequent years?

What if the spiraling out of control that is occurring today - ecclesiastically, morally and doctrinally - was all but inevitable when the idea of a "conference" of bishops was adopted, rather than a "synod" of bishops? What if the willed refusal to face the warn-ings of Lambeth 1930 ("we are a federal organization with no federal government") has found its inevitable outcome in the current Archbishop's recent comment that the "the problems of the Anglican Communion are intractable"? What if the two-fold framework for our communion enunciated in 1930: fidelity to "the Historic Faith and Order of the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic church," as well as "communion with the see of Can-terbury," was being upheld in its entirety, instead of the vain attempt to make it only de-pend on the latter? What if God willed the growth of the Anglican Communion, and in conformity with early Christian History we accepted that in effect a type of "patriarchal see" has been brought forth by the Spirit of God, and that those Bishops in communion with that see must govern collegially for the sake of the gospel of Christ Jesus?

These are some of the questions that are in my mind, as we pass the 150th anniver-sary of the first Lambeth Conference, held from 24 to 27 September,1867. Archbishop Longley invited 150(sic) bishops, and 67 came. The Archbishop of York was vehement-ly opposed and did not come, nor any bishops from his province. The Dean of West-minster refused to allow a service to be held there. By the third Lambeth Conference most invited bishops did attend, but the "tradition" of not being a "synod" was enshrined in the common mind, and ever since that "tradition of men" has trumped every effort to amend the gatherings for the well-being of the whole Anglican Family, at least in a way consistent with the principles of our own English Reformation, let alone the principles of the undivided church.

The very phrase "Anglican Communion" first emerged in 1851, at the 150th anniversary of the Church Missionary Society. It is fascinating to think what might have happened if an intentional missionary vision had prevailed in the subsequent foundation of Lambeth, rather than a cautious compromising inclusiveness? Even so the communion was grow-ing, quite rapidly in some parts of the world, and those who were the spiritual children of the Church of England were asking for unifying guidance. The Canadian House of Bish-ops wrote officially to ask for a "General Council" in 1865. Subsequent appeals were made, but by the middle of the 20th Century that had all died away. "Provincial autono-my" had become the shibboleth. There was no brooking it.

Until the wave of liturgical revision that swept the churches in the 1960's and 1970's, the generally sound biblical theology of the Book of Common Prayer (1662 as norma-tive, with parts of the communion appealing to 1549) held the communion together, at least on the principles of our common doctrine, discipline, and worship. Yet once liturgi-cal revision was let loose - without a global governing structure - the inherent tensions in our doctrinally inclusive communion began to produce a rapid divergence. It became possible to be a very "orthodox" or a very "non-orthodox" Anglican, and to appeal to one of the many theologies now being enshrined in the various prayer books replacing the earlier ones throughout the communion. For many years the "assumed unity" of the Anglican Communion was really rooted in our nearly common liturgy heritage. But the theology undergirding it was rapidly being replaced in some places, and sometimes the consequences were dire. Yet always, in the face of protest and concern, "Provincial Au-tonomy" could be appealed to. Gentlemanly courtesy prevailed for a long time, but that began to blow apart in the 1970's.

Even more division was fostered as the Ordinal of Thomas Cranmer (1550) was re-vised. His ordinal had been kept "sacred" nearly everywhere for over 400 years. It did not get changed, even as other parts of the liturgical inheritance were revised. Its near constant use until the 1970's meant that clergy everywhere in the world had essentially made the same promises. No matter what idiosyncratic (if not heretical) views emerged here or there, the biblical Ordinal of Cranmer united all the faithful ordained leaders of the churches of the communion. Men of integrity were accountable to the vows they had made.

The 1976 revised ordinal of the Episcopal Church became the main instrument for un-dermining the unity of the faith of the church in the United States, and the drastic con-sequences for the global Anglican Family are still unfolding. None of this could have happened if there was a recognized global governance among us, committed to the truths of the English Reformation, and the "historic Faith and Order" we once all agreed we held in common. But with the now enshrined "doctrine of provincial autonomy" there was no way to stop the ever increasing departure from the "faith once delivered" in many parts of the Anglican Communion. Today, in much of the developed world, what was nearly universally believed by our ordained leaders is an embattled minority opin-ion.

Is there any way to reverse these sad trends?

The Lambeth Quadrilateral, enunciated in 1888 and widely acknowledged still as some-how central to our fragile unity, provides an interesting possibility. Should we actually uphold it as a "minimum" for inclusion in the communion? If we did there would be a framework for rethinking what was meant by Thomas Cranmer asking if all clergy would be "faithful to the doctrine, discipline, and worship of Christ, as this church...has re-ceived them?" Are the changes we have faced, and that may be proposed, consistent with fidelity to the Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments? Has it remained true that they are "the rule and ultimate standard" of the faith? Are we living in fidelity to the creeds because they are faithful to the Holy Scriptures? Are we upholding the scrip-tural truths enshrined in the liturgies of Holy Baptism and Holy Communion? are we ac-tually staying true to the "historic episcopate" or has it become among us a clay nose, to be made whatever we want it to be?

It is certainly possible to argue, and I believe correctly, that the fathers of Lambeth in 1888 were not for one-minute imagining what we have made of the fourth article of the Lambeth Quadrilateral. The 'adaptation' they had in mind was that which had produced the English system of primate, archbishops, bishops, archdeacons and deans - when there had only been bishops, presbyters, and deacons at the beginning of the church's life. They meant jurisdiction based on geographical provinces and diocese, when the beginning was always a small local "parochia." Doubtless some of them wanted to simplify this evolved system, and some were even willing to discuss to what extent some non-episcopal churches had a form of this ancient inheritance which could be rightly accepted in a reuniting church. But they were not suggesting that what the apos-tles began with the authority of the Lord, what Holy Scripture bears witness to, and what became the universal pattern of the church universal, could be manipulated so as to make it's fundamental service "changing" the church's doctrine, order, and discipline rather than "upholding" it.

Would the calling of an Anglican General Council be contrary to the Lambeth Quadri-lateral? More importantly, would it be contrary to the Holy Scriptures? The apostle Paul seem to think that the church in Corinth was capable of deciding disputes faithfully. "Is there no one wise enough" among you able "to settle a dispute between the brothers?" Can not the Anglican Family find a way to settle disputes in a manner consistent with the unity of the early church and Holy Scripture? Are we to continue in a compromising stew of committees and papers that almost no one reads and which almost all ig-nore?Dare we claim we are a global family - that can call itself "the Anglican Church" - if we have no true Faith and Order that we all submit to? Is such a "federated church" re-ally one which is faithfully "submit[ing] to Christ" as the Apostle so clearly assumed was true of all those called by him into the fellowship of his church? Dare we claim to be "upholding the doctrine, discipline, and worship of Christ" as it was received in England so long ago?

What if the Primates took courage and called for a global Synod of Anglican Bishops with Jurisdiction? What if they refused to countenance our devolution into a scattered body of competing churches and splinter groups, some better called sects than Chris-tian churches?

Should we have a global Anglican General Council in 2020, or just another conference?

Jon Shuler

(c) Crossgate Resources